By now, I hope you can tell that:

- I love to cook

- I love my Korean heritage

- This class is inspiring new recipes!

Therefore, how can I do research on anything other than Korean-Mexican fusion food and the influences of Asia on Mexico (and vice versa)?! In my first assignment, I touched upon mole poblano, which is a blending of a variety of ingredients with the main focal point of chocolate (for that specific type of mole). Then, we moved to tamales for the second assignment, a once popular street food from the famous tamale man, to a now underrated meal of delight, filled with wonderous simplicity. If I can dive into poetics, I think I’m realizing my need to uncover what “blending together” means. What does it mean to mix? Like mole poblano, my interests are complex – I am intrigued by the conglomeration of ingredients, the deep richness of its intricate meshing – yet, like a tamale, all I have to do is surpass the unsuspecting corn husk or banana leaf wrapping to find something exquisitely digestible. So, together, let’s find out more about the friendship turned to love of two worlds geographically separated, yet historically tied.

GASTRODIPLOMACY + FUSION

Beginning on the more academic side, in Paul S. Rockower’s article, “Recipe for gastrodiplomacy,”gastrodiplomacy is “how countries conduct diplomacy through promotion of their cuisine . . . [it’s] the act of winning hearts and minds through stomachs” (235). It’s considered a branch of public diplomacy, but more intimate, with more protocols on how to proceed in such relations. Here, Rockower lays out the way food dives deeper than small-talk or conversations on facts or data. No one care about the numbers, but everyone cares about a good, warm meal after a long day at work. Why does this even matter to Asia or Mexico, though? Well, “gastrodiplomacy has become a public diplomacy strategy, most commonly found in East and Southeast Asia . . . Seoul, [South Korea] initiated the ‘Korean Cuisine to the World’ campaign in April 2009, with stated goals of increasing Korean restaurants abroad fourfold to nearly 40,000 by 2017” (238-239). Rockower details how Koreans in Los Angeles even began their own community spread of culture and diplomacy through tacos. “The Korean taco truck became synonymous with the Korean food craze in the United States” (239). So…Mexican style cooking actually helped push South Korean cuisine into the United States’ markets? Say whaaaa?! The article keeps going with more examples of gastrodiplomacy in more East and Southeast Asian countries. Rockower promotes this spread of cuisine as something other than the term we see everywhere: “fusion.” This does not technically talk about the mixing of people or the great “American melting pot,” but it shows how there is a push for countries to become globally recognized for their food, even if it means shaking up the way it is served to get people to try it.

Although gastrodiplomacy may have been invented in the 21st century, fusion has been happening since America started forming into a country. In the LA Times article, “Fusion Food : Birth of a Nation’s Cuisine : Food History: The adapting of ingredients and dishes from other cultures is nothing new in American cooking. In fact, it’s as old as macaroni and cheese and chili con ‘cana,’” Perry lays out the way Italian cuisine was once for the rich, but turned quickly into an accessible “American” flavor. Unsurprisingly, he then touches upon the way Mexican food started out in white cookbooks, being labeled as “Spanish Dishes.” Though already being morphed into an easier format, there was a lack of Mexican ingredients to supplement the cuisine’s growing popularity:

“Tortillas were not available in stores. Recipes in The Times cookbook explained how to roll out flour dough “the size of a dinner plate” and fry it (or even deep-fry it) to make tortillas. . . Ground chile, for instance; most recipes required soaking whole dried chiles and scraping the flesh from the skin. Oregano was not widely known–several recipes call for sage instead. Cumin, though known, was hardly ever called for in the recipes. However, chili powder (containing cumin and cinnamon) was already on the market, expressly for flavoring chili con carne.”

This article was a great start into understanding fusion food more, but because it was published in 1993, the ending paragraph made me chuckle. I guess back then, fusion food was becoming steadily popularized. Perry says, “we’ll probably look back on today’s cookbooks and realize that a lot of the recipes we thought of as hyper-authentic in 1993 had actually been subtly adapted to our own kitchens and our own tastes.” Why yes, Mr. Charles Perry, is anything truly “authentic” anymore?

COMMUNITIES ALONG THE BORDERS

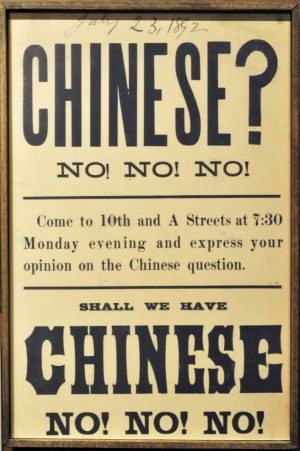

Speaking of fusion history, not every cuisine and culture was welcomed with open arms, and as we understand from before, if they were accepted, they were transformed into something less “intimidating” to the American public. Lisa Morehouse from NPR’s publication The Salt dives into China’s relations with Mexico. She reveals how if you want the best Chinese flavors, you need to cross the border into Mexico. That’s right! Instead of finding their way to Angel Island, Chinese Immigrants were banned from the United States in 1882 for a period of 10 years (history.state.gov). “Spurred by anti-Chinese laborer sentiment among American workers . . . thousands went to Cuba, South America and Mexico instead. Many settled along the U.S.-Mexico border, becoming grocers, merchants and restaurant owners.” This then spurred a fusion blend of Chinese Mexican cuisine. In the article, Morehouse focuses on a specific restaurant, explaining how the kitchen speaks Cantonese while the waiters and external staff speak Spanish and English. The flavors are different from “true” Chinese food because of the resources available. They didn’t have the same produce or spices that they had back at home and therefore, they had to improvise. Although the two countries seem like unlikely besties, “If you ask people in the city of Mexicali, Mexico, about their most notable regional cuisine, they won’t say street tacos or mole. They’ll say Chinese food.” So it seems like an unfortunate ban of a certain “kind” of people just redirected them elsewhere. It is easy to note, though, after going through this Taco Literacy course, that we can see food patterns by looking at the history of migration.

SO UH…KOREANS AND MEXICANS?!

As I said in the beginning, I am Korean (or I consider myself a Korean-American), so of course, we need to talk more about my people! Now that you have more of a background on how cultures began coming together, especially in Mexico, we can discuss in-depth the Korean migration movement and immigrant mindset. John T. Edge lays out what I like to think is the most detailed history of the Korean taco truck in his article, “The Tortilla Takes a Road Trip to Korea.” Kogi, the famous Ko-Mex food truck that started it all, sparked the nation into a frenzy. “Eighteen months later [after Kogi’s beginning in November 2006], dozens of entrepreneurs across the country [began] selling Korean tacos. Like Buffalo wings and California rolls, Korean tacos have gone national, this time with unprecedented speed.” Edge lays out all the different names of the businessmen and women in the Korean taco truck market as well as each of their truck names and locations. All of them seem to have one theme. It’s Korean meat (bulgogi or galbi/kalbi) wrapped in a tortilla or stuffed into a burrito. Each business has their own twist, but that’s mostly it. The article also transparently reveals each entrepreneur’s ethnic background – whether they were born in America with Korean parents or Korean native and raised in American culture. This seems key to understanding how each truck’s story came about. Some were in it for the money while others saw an opportunity to take the food that they love at home, (cooked by their umma), and blend it with the culture they’ve grown up in. From 2010, this New York Times article may need to be updated now. As 10 years have gone by, I think there’s been even more growth in Ko-Mex cuisine.

Yet, as much as we are in desperate need for an updated list of Korean Mexican taco trucks, we need to understand more of the inspiration of what sparked Korean’s interest in Mexican food. That’s why I have come to love the New York Times for their other article on this Korean Mexican blend called “For a New Generation, Kimchi Goes With Tacos,” by Jennifer Steinhauer. (Also, have you noticed that these names don’t sound Korean? A little concerning, no?). Anyways, this article strays away from the listing of trucks and gives more of a deeper dive onto WHY those trucks began in the first place, starting with the history of the infamous Kogi. “The chef Roy Choi, 38, who began his career at Le Bernardin in New York and worked as the chef in several Los Angeles restaurants, including RockSugar, found himself out of a job and running out of cash. He had coffee with Mark Manguera, a former co-worker, who suggested that they operate a taco cart with a Korean twist.” According to Steinhauer, there was a shift in the past couple years (when it was 2009) where second-generation Koreans began gravitating to “tech-boom” money and Korean parents’ perspectives on cooking as a profession began changing. I love reading about this switch, especially as a first-generation Korean daughter living and seeing the realities of the generational switches. The article quotes professor of ethnic studies at UC Riverside, Edward Chang, saying, “The first generation of Korean immigrants here mainly catered toward a Korean clientele, or made grocery markets catering to a minority clientele, but more recent immigrants have ethnic and capital resources that enable them to branch out in the mainstream economy.” This could possibly be why the 10s decade with filled with a plethora of new fusion foods. From experience, I’ve not only seen Korean tacos, but burgers stuffed in naan bread and steak cheese wontons.

Other than Koreans in America being inspired by Mexican food, Koreans in Korea have also been moved by the cornspiration. Erik Ortiz from NBC News gives an overview on the Korean Californian and Korean Texan friends who needed to bring some of their childhood memories with them to the motherland. Living in Seoul, they actually missed some of their Southwestern flavors and realized they needed to be the ones to bring their wishes to life. Now, their world-renowned restaurant, Vatos Urban Tacos, has had guests like Secretary of State John Kerry and U.S. Ambassador to South Korea, Mark Lippert. In the article, Ortiz interviews one of the owners, Sid Kim, asking him questions like “why those two specific cultures?” to “do you see culture difference in customers?” Kim’s response is something I feel like needs to be put on every wall. This is the epitome of mixed kids. “When I came home after school, I would look into the fridge to grab a bite to eat, and I’d almost always see some leftover Korean food that my mom had cooked the night before . . . Since I was a kid, I would grab a tortilla, throw in those ingredients, and there you have it — Ko-Mex fusion food. To be honest, I don’t particularly like the world “fusion” to describe the food at Vatos. Fusion to me implies some sort of forced combination. Things like galbi tacos, bulgogi sandwiches, pork belly burgers and kimchi pizzas aren’t fusion foods. To me, they are just food — the food I grew up on.” After reading through my research, what do you think? Is fusion forced or is its connotation supposed to reference something natural? It seems inevitable that an ever-globalizing world will continue to mush cultures and cuisines together, so do we have to label these foods as specifically Korean-Mexican or French-Chinese? This begins to make me think…what do these labels in themselves hold? What images do you see when you think of these labels? Can I ever make a dish called “American” if I add a bunch of ingredients together from my Korean and French heritage? Does it have to be French-Korean?

Works Cited

Edge, John T. “The Tortilla Takes a Road Trip to Korea.” The New York Times. 27 July 2010. Accessed 23 April 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2010/07/28/dining/28united.html.

Morehouse, Lisa. “The Chinese-Mexican Cuisine Born of U.S. Prejudice.” NPR The Salt. 16 April 2015. Accessed 23 April 2020. https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2015/04/16/399637724/the-chinese-mexican-cuisine-born-of-u-s-prejudice.

Office of the Historian. “Chinese Immigration and the Chinese Exclusion Acts.” Milestones: 1866-1898. United States Department of State. Accessed 23 April 2020. https://history.state.gov/milestones/1866-1898/chinese-immigration

Ortiz, Erik. “Seoul’s Korean-Mexican Food Revolution is Being Led by Americans.” NBC News. 28 Aug. 2015. Accessed 23 April 20. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/asian-america/korean-mexican-food-revolution-being-led-american-owned-vatos-seoul-n416021

Perry, Charles. “Fusion Food : Birth of a Nation’s Cuisine : Food History: The adapting of ingredients and dishes from other cultures is nothing new in American cooking. In fact, it’s as old as macaroni and cheese and chili con “cana.” LA Times. 16 Sept. 1993. Accessed: 23 April 2020. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1993-09-16-fo-35521-story.html

Rockower, Paul S. “Recipes for Gastrodiplomacy.” Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, vol. 8, no. 3, 2012, pp. 235-246. ProQuest, https://jerome.stjohns.edu/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.jerome.stjohns.edu/docview/1236699020?accountid=14068, doi:http://dx.doi.org.jerome.stjohns.edu:81/10.1057/pb.2012.17.

Steinhauer, Jennifer. “For a New Generation, Kimchi Goes with Tacos.” The New York Times. 24 Feb. 2009. Accessed 23 April 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2009/02/25/dining/25taco.html